A Guide to Michelin's Three-Star Restaurants

Le Cinq in Paris is among 109 restaurants in the world that won three Michelin stars in 2016. / Courtesy of Andy Hayler

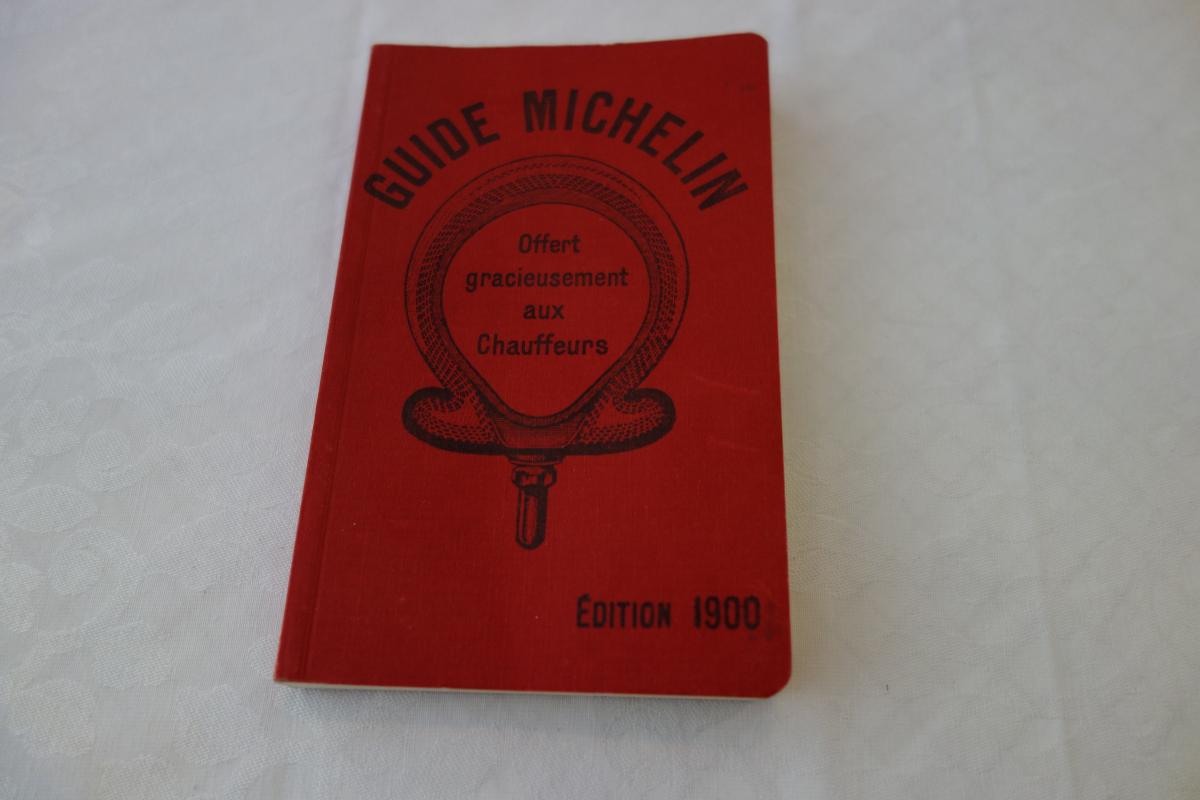

It is a quirk of history that the planet’s most respected food guide is run by a tire company. In 1900, the automobile was a leading-edge technology that had been around for just 15 years. Andre and Edouard Michelin ran a rubber factory in France and patented the removable pneumatic tire in 1891. They wanted to promote their company and, at the turn of the century, came up with the idea of a travel guide to France, listing within its pages garages and mechanics as well as hotels and restaurants – everything a new car owner might need.

The Guide Michelin premiered in France in 1900. / Courtesy of Andy Hayler

At that time, there were just 3,000 cars in the country. The Michelin Guide, with its distinctive red cover, became an annual publication and an indispensable companion for travellers exploring the French countryside. Eventually the geographic scope was extended: The Michelin Guide to Spain appeared in 1952, then to Italy in 1956. By 1974, it had even reached that murkiest culinary corner of Europe, Great Britain. The Guide spread its wings beyond Europe in 2006 with its New York edition, and rapidly spread through much of Japan, Hong Kong and Macau and, most recently, Sao Paolo and Rio de Janeiro.

The reason the Michelin Guide has attained its position is its independence and easy-to-understand star rating system for restaurants. Michelin employs full-time inspectors (mostly ex-hoteliers and chefs) who visit establishments anonymously and, crucially, pay their own bills. The vast majority of restaurant guides rely on freebies from restaurants, charge fees or accept advertising, all of which can compromise their assessments. Because Michelin regards the guide as a marketing overhead, they can afford the considerable costs associated with its inspection process.

The Michelin star was introduced in 1926. By 1933, the familiar one-, two- and three-star system was adopted and has remained unchanged to this day. A star means “very good cooking in its category.” Two stars means “excellent cooking, worth a detour.” And the ultimate third star means “exceptional cuisine, worthy of a special journey.”

By early 2016, there were 109 restaurants in the world that held the three-star accolade. By comparison, in 2004 there had been just 49 three-star restaurants, all in Europe.

One of Andy Hayler's most memorable meals was at Mizai, a six-seat Kyoto restaurant. /Andy Hayler

In 2004, I completed a tour of all those restaurants, and have kept up date with Michelin periodically ever since. For example, I went to all 110 three-star establishments that existed in 2014.

A Michelin three-star restaurant should represent the ultimate food experience that can be found. Due to the difficulty in attaining a Michelin star, it has become the ultimate currency in the restaurant world. There are certainly other guides, many of them influential, but few have such wide global coverage and none have managed to maintain Michelin’s reputation for integrity. You cannot pay a public relations company a large sum of money to get you a Michelin star. It must be earned. Certainly some of Michelin’s assessments are controversial, and there are many I would personally disagree with, but they are at least honest judgements rather than a function of marketing expenditure. To adapt Winston Churchill’s famous dictum on democracy as a form of government – Michelin may be the worst of all restaurant guides, except all others that have been tried.

Considerable speculation and mythology exists about what it takes to earn a star, or indeed three. Michelin, probably wisely, has remained silent on the specifics of its assessment system. At one time, restaurateurs assumed grand dining rooms and expensive glassware were a prerequisite. But this view is refuted if you examine some counter-examples.

Sushi Saito earned three Michelin stars when it was encased in a Tokyo car park. / Courtesy of Andy Hayler

Sushi Saito was, until recently, located inside a Tokyo municipal car park behind an unmarked door leading to a plain wood counter with six seats: no Riedel glasses or dinner-jacketed maître d’s here. Yet it has three Michelin stars for serving what many regard as the best sushi in Japan. Three-star Aqua in Wolfsburg is located next to a car factory, so glamorous locations are clearly not required.

Auberge de l’Ill in Alsace has a gorgeous river view framed by a willow tree. / Courtesy of Andy Hayler

There are certainly some spectacular locations for three-star Michelin restaurants. Le Petit, Nice is built on cliffs overlooking the azure Mediterranean, and Auberge de l’Ill in Alsace has a gorgeous riverside view framed by a huge weeping willow. However, the most spectacular must be Michel Bras in Toya, awarded three stars in the one-off Hokkaido guide of 2012. In a hotel that stands solitary perched on the rim of a volcano, the restaurant overlooks the crater’s lake and, in the opposite direction, the Pacific Ocean.

The food is as stunning as the view at Michel Bras in Toya, which overlooks a volcano and the Pacific. / Courtesy of Andy Hayler

Michelin’s assessments are frequently controversial and assessing a restaurant is not a science. If the guide’s great strength is its independence from the restaurants it assesses, it nonetheless seems to have some systematic issues. In general, it is slow to give stars and slow to take them away, perhaps conscious of the effect they have on the revenue of a restaurant. Restaurateurs have reported a 20- to 30-percent increase in revenue when they win a star, with a similar effect if they lose one.

Although in Europe at least they reportedly employ some inspectors in a cross-border capacity to conduct quality control, there nonetheless seems inconsistency in the standards applied country by country, something Michelin denies. I find the USA and UK to be more kindly marked than Germany and France, and the Hong Kong guide to be utterly baffling in its scoring. There is also a geographic limitation. Michelin only covers certain locations. If you happen to have a great restaurant outside the geographic remit of Michelin, that’s tough. No stars for you. This is one reason why alternative lists and guides, which do not require the substantial costs of a team of employed anonymous inspectors, have become popular.

Michelin continues to expand in fits and starts. It dropped a guide to Las Vegas and Los Angeles due to poor sales, but there will be a 2017 guide to Singapore.

Some of the best modernist cuisine in the world is offered at Alinea’s in Chicago. / Courtesy of Andy Hayler

Of all the Michelin-starred restaurants in the world, what is the best? Inevitably this is subjective, depending on the personal preferences of each of us. I enjoy classical cooking whereas others prefer cutting-edge modernist cooking. The best of the latter can be found at Alinea in Chicago, and further back could be experienced at Sergio Herman’s Oud Sluis in Flanders, which closed at the end of 2013. The best of all, for me, was delivered by Marc Veyrat, an eccentric genius, always dressed head to toe in black, who conjured up magical modern food in Lake Annecy and Megeve in the late 1990s.

Robuchon’s sous chef, Franky Semblat, cooks at the Robuchon au Dome in Macau. / Courtesy of Andy Hayler

For myself, I have never had better food than that produced at Jamin in Paris when Joel Robuchon was at the height of his culinary powers. Of current restaurants, there are a few that I particularly like. Robuchon’s sous chef was Francky Semblat, who cooks at the Robuchon au Dome in a glitzy dining room at the top of a casino in Macau. He still demonstrates the precision and gift with ingredients (many imported from Japan) he learned at Jamin.

In Japan, I have particularly fond memories of Mizai, a six-seat Kyoto restaurant producing kaiseki dinners, the ultimate expression of seasonal tasting menus. Perhaps the most flawless classical cooking was to be found at Hotel de Ville, whose chef Benoit Violier tragically shot himself in January 2016. The restaurant continues under Franck Giovannini.

Some of the world's finest classical cooking is at Hotel de Ville in Switzerland. / Courtesy of Andy Hayler

Le Calandre is in a wildly unpromising location in a dull industrial town called Rubano in northern Italy. Its chef, Massimiliano Alajmo, is the youngest chef ever to gain three Michelin stars (at just 28). He switches effortlessly between classical Italian regional dishes and experimental modern cooking, demonstrating complete mastery of both. Some of the best three-star restaurants are in Germany, and I particularly like Schloss Berg near the border with Luxembourg, where Christian Bau combines classical culinary technique with a fascination with Japanese ingredients cooking, a rare example of fusion cooking without confusion.

Les Pres Eugenie in France has maintained three Michelin stars since 1977. / Courtesy of Andy Hayler

Although Paris has less Michelin stars than Tokyo, in 2016 it still retains 10 restaurants with a lustrous three stars, and restaurants such as Guy Savoy produce terrific food. However, my current favorite in the world is not in Paris but at Les Pres Eugenie in a tiny village called Eugénie-les-Bains. Michel Guerard has retained three stars since 1977 and, at the age of 83, the sprightly chef can still be seen in his kitchen every day, ensuring his exacting standards are met. Once seen as a radical innovator for championing a lighter, healthier style of cooking, he now makes the most of the superb local produce of the south of France, cooking deceptively simple yet perfect meat and shellfish dishes. I ate five meals here in 2015 alone, and for me there is no better restaurant in the world today.

Category:

Recommended features by ExtremeFoodies